Cloud Costs Are Out of Control — Nobody Talks About It

Cloud computing was sold as a revolution: infinite scalability, lower upfront costs, and the freedom to pay only for what you use. For a while, that promise seemed real. Startups scaled quickly, enterprises migrated aggressively, and cloud providers positioned themselves as the backbone of the modern internet. But quietly, year after year, something changed. Cloud bills started rising faster than expected, faster than revenue, and faster than anyone wanted to admit. Today, many organizations are facing what can only be described as a cloud cost crisis.

What makes this crisis particularly dangerous is how normalized it has become. Cloud overspending is no longer viewed as an anomaly or a temporary inefficiency. Instead, it is treated as the unavoidable cost of doing business in a cloud-first world. Few companies talk about it openly, fewer share real numbers, and almost none challenge the underlying assumptions that created the problem in the first place.

The Internet Feels Worse Than It Did 5 Years Ago — Here’s Why

The Pay-As-You-Go Illusion

The original appeal of cloud computing was financial flexibility. Instead of purchasing servers and networking hardware upfront, businesses could rent computing power on demand. This pay-as-you-go model sounded inherently efficient. In theory, you would only pay for resources when they were actively used. In practice, this model introduced a level of complexity that most organizations were not prepared to manage.

The cloud cost crisis begins here. Cloud services charge by the second, minute, or hour across dozens of dimensions: compute, storage, data transfer, API calls, managed services, backups, and more. Each individual charge seems small. Combined across thousands of services and millions of requests, costs spiral out of control. Unlike traditional infrastructure, there is no obvious “full capacity” signal. The meter is always running, quietly accumulating charges in the background.

Why Cloud Bills Keep Growing Even When Usage Stays Flat

One of the most confusing aspects of modern cloud spending is that costs often increase even when user growth slows or stabilizes. Companies report higher monthly cloud bills without corresponding increases in traffic, customers, or product usage. This phenomenon fuels the perception that the cloud is unpredictable or inherently expensive.

The reality is more structural. Cloud providers continuously introduce new managed services, security layers, monitoring tools, and redundancy features. Engineering teams adopt them incrementally, often without fully understanding their cost implications. Over time, architectures become bloated. Services overlap. Resources are duplicated “just in case.” Each decision makes sense in isolation, but collectively they deepen the cloud cost crisis.

The Hidden Cost of Convenience

Managed services are one of the cloud’s most seductive offerings. Databases, queues, authentication systems, analytics pipelines, and AI services can be spun up in minutes. No maintenance, no patching, no hardware planning. The tradeoff is cost opacity.

When teams used to manage their own infrastructure, performance tradeoffs were visible. Scaling meant buying hardware. Now, scaling is abstracted behind a slider or configuration file. This abstraction hides inefficiencies. Engineers optimize for reliability and speed, not cost. Over time, convenience-driven decisions accumulate into massive recurring expenses that are rarely revisited.

This is a central driver of the cloud cost crisis: the decoupling of engineering decisions from financial consequences.

FinOps Exists — But It’s Not Solving the Problem

In response to rising cloud costs, many organizations have adopted FinOps practices. FinOps aims to align finance, engineering, and operations around shared responsibility for cloud spending. Dashboards are created. Alerts are configured. Monthly reviews become standard.

While FinOps helps with visibility, it often fails to address root causes. Engineers still prioritize delivery speed. Product teams still demand scalability. Leadership still pushes cloud-first mandates. FinOps teams frequently become cost reporters rather than cost preventers. They explain why bills are high, not why architectures were allowed to become inefficient in the first place.

As a result, FinOps slows the growth of the cloud cost crisis, but rarely reverses it.

Vendor Lock-In Makes Costs Harder to Escape

Once a company commits deeply to a cloud provider, leaving becomes prohibitively expensive. Services are tightly integrated. APIs are proprietary. Data egress fees punish migration. Even partial moves introduce operational risk and retraining costs.

This lock-in shifts negotiating power entirely to cloud vendors. Pricing changes are accepted, not challenged. New billing dimensions are added gradually, making them harder to track. Over time, organizations stop asking whether the cloud is cost-effective and start asking how to survive the next billing cycle.

The cloud cost crisis is not just a budgeting problem; it is a strategic dependency problem.

Engineering Incentives Fuel Overspending

Most engineering teams are not incentivized to care about cloud costs. Performance reviews reward feature delivery, uptime, and scalability. Cost efficiency is rarely a primary metric. In some organizations, it is not measured at all.

When engineers are told to “make it scalable” or “design for growth,” the safest option is overprovisioning. More replicas, larger instances, multi-region redundancy. These decisions reduce risk and pager alerts, but they increase cost dramatically. Without clear ownership of spending, cloud usage grows unchecked.

This incentive mismatch is one of the least discussed aspects of the cloud cost crisis.

Startups Feel the Pain First — Enterprises Feel It Later

Startups often encounter cloud cost issues early because infrastructure expenses represent a larger percentage of their burn rate. A sudden spike in cloud spending can shorten runway by months. Many founders are shocked to learn that their infrastructure costs scale faster than revenue.

Enterprises, on the other hand, absorb cloud costs more easily at first. Budgets are larger. Bills are spread across departments. But eventually, even large organizations hit a tipping point. Cloud becomes one of the largest line items in IT spend, rivaling payroll or real estate. At that stage, reversing course is slow, expensive, and politically difficult.

The cloud cost crisis does not discriminate by company size. It only differs in how long it takes to become visible.

Data Transfer: The Silent Budget Killer

Compute and storage costs receive the most attention, but data transfer is often the real culprit behind unexpected bills. Moving data between regions, services, or out of the cloud incurs fees that are easy to overlook during design.

Modern architectures rely heavily on microservices, APIs, and distributed systems. Each interaction may involve data movement. Individually trivial, collectively massive. Data egress fees, in particular, discourage hybrid or multi-cloud strategies, further reinforcing vendor lock-in.

In many organizations, data transfer costs are the fastest-growing component of the cloud cost crisis, yet they are the least understood.

Observability Costs More Than the Systems Being Observed

Logging, monitoring, and tracing are essential for modern systems. But observability tools themselves have become major cost centers. High-cardinality logs, long retention periods, and verbose tracing generate enormous volumes of data.

Teams often enable maximum observability by default, fearing outages or blind spots. Few revisit these settings once systems stabilize. Over time, observability costs quietly exceed the cost of the infrastructure they are monitoring.

This irony is emblematic of the cloud cost crisis: tools designed to improve reliability end up undermining financial sustainability.

The Myth of Infinite Scalability

Cloud marketing emphasizes limitless scale, but real-world businesses do not need infinite capacity. Most workloads follow predictable patterns. Traffic spikes are often seasonal or event-driven. Yet systems are architected as if sudden, massive growth is always imminent.

This mindset leads to persistent overprovisioning. Resources sit idle “just in case.” Autoscaling rules are conservative. Redundancy is layered without periodic reevaluation. Each choice feels prudent, but together they form a bloated, expensive infrastructure footprint.

The cloud cost crisis thrives on worst-case thinking.

Why Nobody Wants to Talk About It

Cloud spending is an uncomfortable topic. Admitting that costs are out of control implies poor planning, weak governance, or flawed strategy. For leadership, it challenges years of cloud-first messaging. For engineers, it raises questions about architectural decisions. For vendors, it threatens revenue growth narratives.

As a result, cloud overspending is discussed in private meetings, not public case studies. Failures are reframed as “learning experiences.” Cost overruns are attributed to growth rather than inefficiency. The silence allows the cloud cost crisis to continue unchecked.

Cost Optimization Often Conflicts With Reliability

Reducing cloud costs is rarely straightforward. Downsizing instances, reducing redundancy, or shortening log retention all introduce perceived risk. Teams fear outages, data loss, or slower incident response. In regulated industries, compliance requirements further limit optimization options.

This tension creates inertia. Even when costs are clearly excessive, organizations hesitate to act. Stability becomes the justification for inefficiency. Over time, high costs are accepted as the price of safety.

This tradeoff is real, but it is also frequently exaggerated. Many organizations overpay not for reliability, but for peace of mind.

Cloud Providers Benefit From Complexity

Cloud pricing is intentionally complex. Dozens of service tiers, discounts, reservations, savings plans, and region-specific rates make accurate forecasting difficult. Complexity discourages comparison and migration. It also shifts responsibility onto customers to “optimize” usage.

From a business perspective, this complexity is effective. From a customer perspective, it fuels the cloud cost crisis by making overspending easier than optimization.

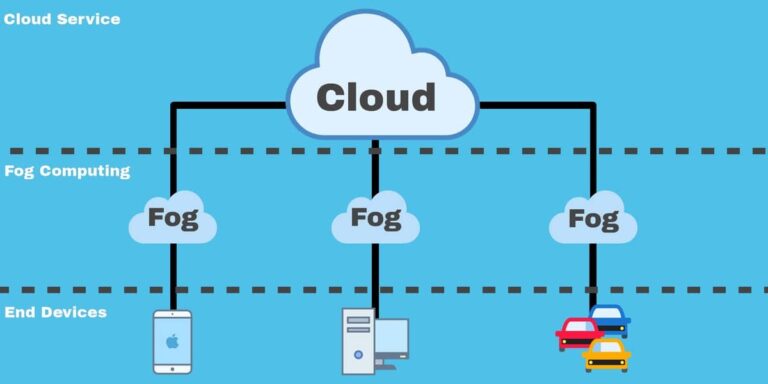

The Rise of Cloud Repatriation

In recent years, some companies have begun moving workloads back on-premises or to hybrid models. This trend, sometimes called cloud repatriation, reflects growing dissatisfaction with cloud economics rather than performance.

Repatriation is not a rejection of cloud technology, but a recalibration. Certain workloads are cheaper and more predictable on owned infrastructure. Others benefit from cloud elasticity. The key lesson is that cloud is not always the cheapest option.

The cloud cost crisis has forced organizations to rethink the assumption that cloud is the default answer to every problem.

What the Cloud Cost Crisis Reveals About Modern Tech Culture

At its core, the cloud cost crisis is not just a financial issue. It reflects deeper cultural patterns in modern tech: speed over discipline, abstraction over understanding, and growth over sustainability. The cloud made it easy to build powerful systems quickly. It also made it easy to ignore long-term consequences.

As organizations mature, these tradeoffs become harder to ignore. Cloud costs expose architectural debt, incentive misalignment, and strategic complacency. They force uncomfortable questions about how technology decisions are made and who is accountable for their outcomes.

The cloud is still a powerful tool. But without deliberate restraint, it becomes an expensive one.

FAQ — Cloud Cost Crisis

Q1: What is a cloud cost crisis?

A cloud cost crisis occurs when organizations’ cloud spending grows uncontrollably, often outpacing revenue or budget expectations. It results from mismanagement, overprovisioning, lack of cost visibility, and architectural inefficiencies.

Q2: Why are cloud costs so hard to control?

Cloud bills are complex, with multiple dimensions like compute, storage, data transfer, managed services, and monitoring. Organizations often lack visibility or accountability for these charges, contributing to the cloud cost crisis.

Q3: Can cloud cost optimization tools solve the problem?

Tools help identify inefficiencies but cannot solve underlying architectural or cultural issues. Optimization must be paired with governance, cost awareness, and cross-team accountability.

Q4: Are some clouds cheaper than others?

Pricing varies by provider, region, and service type. While vendor choice impacts costs, overspending is more often caused by uncontrolled usage rather than pricing alone. Vendor lock-in can also worsen the cloud cost crisis.

Q5: What are common mistakes that worsen cloud costs?

- Overprovisioning resources

- Ignoring idle instances or unused services

- High retention of logs and data

- Lack of accountability for teams consuming cloud resources

- Relying solely on default configurations

Conclusion

The cloud cost crisis is not just a budgeting issue—it is a strategic and cultural problem. Cloud computing remains a powerful enabler for innovation, but unchecked adoption and poor cost governance have created widespread inefficiencies. Organizations that rely solely on FinOps dashboards, superficial reporting, or vendor-provided tools risk paying far more than necessary.

Real solutions require a combination of architectural discipline, cost-aware culture, proper incentives, and continuous monitoring. Cloud is transformative, but without strategic cost management, it becomes a financial burden rather than an advantage.